Iran's president and foreign minister have died. What happens next?

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and his foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian passed away on 19 May 2024 after the helicopter carrying them crashed. The two were accompanied by seven other senior officials and government personnel including Malek Rahmati, governor of East Azerbaijan province, and Mohammad Ali Al-e Hashem, the Friday prayer leader of Tabriz.

The cause of the crash remains unknown but bad weather, poor visibility, difficult terrain, or pilot error may have individually or collectively been at fault.

Javad Zarif, the previous foreign minister under the government of President Hassan Rouhani, has suggested that economic sanctions may have been at fault, but no clear evidence that this was the case has emerged.

President Raisi and Amir-Abdollahian were part of a larger Iranian delegation that had visited the border area with the Republic of Azerbaijan earlier that day to inaugurate the the jointly built Qiz Qalasi dam alongside President Ilham Aliyev.

President Raisi and the others subsequently departed on a Bell 212 helicopter at the end of the inauguration ceremony and crashed shortly thereafter. News of the disappearance of the helicopter and its passengers sparked large-scale search that lasted nearly 12 hours before the wreckage and bodies were found.

Iran received international support to locate the helicopter crash site, including activation of the Copernicus EMS rapid response satellite mapping service by the European Union at Tehran’s request, and assistance by the Akinci unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) from Turkey. Turkish media claimed that the Akinci drone was the first to locate the crash site and relay its coordinates to Iranian authorities.

The General Staff of the Armed Forces denied this and put out a statement on 22 May claiming the Turkish drone failed to accurately pinpoint the location of the helicopter crash site due to the lack of equipment for the “detection and control of points under clouds” and returned to Turkey. It instead asserted that the crash site was located by Iranian drones equipped with synthetic-aperture radar (SAR).

Major General Mohammad Bagheri, the chief-of-staff of the Armed Forces, launched an investigation of the crash on the morning after and appointed a high level group including civilian and military experts under Brigadier General Ali Abdollahi, the deputy for coordination of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, to carry it out.

Iranian Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei urged the public “not to worry” following the crash and assured them that “there will be no disruption in the work of the country.”

But Iranians and the international community are left with many questions about this incident, including who were President Raisi and Amir-Abdollahian, what happens next in Iran’s politics, and what are the possible implications for the country’s future?

Who was President Ebrahim Raisi?

Ebrahim Raisi was born to a clerical family in the shrine city of Mashhad, Khorasan province, in 1960. He pursued a traditional Shia religious education as a child and young adult. The level of his educational attainment and religious credentials were a subject of controversy in his lifetime.

Raisi was politically active as a supporter of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini during the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Soon after he began his career in the judicial system of the newly established Islamic Republic and quickly ascended its ranks.

Around this time, Raisi married Jamileh Alamolhoda, the daughter of the influential ultraconservative cleric Ayatollah Ahmad Alamolhoda, with whom he had two daughters. He became part of an influential network centered on Mashhad and Khorasan Razavi province, from which other senior figures also hail, including Ayatollah Khamenei, speaker of parliament Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, and Islamic Revolution Guard Corps Jerusalem Force (IRGC-JF) commander Brigadier General Esmail Ghani.

He was appointed as the deputy prosecutor of Tehran in 1985, and it was in this role that he is believed to have played a central role in one of the darkest episodes of the post-revolution system in Iran: The mass execution of political prisoners in 1988.

Despite this ignominious background, or perhaps because of it, he would go on to have a successful career in the judicial system, including serving as the prosecutor-general from 2014 to 2016, and chief justice from 2019 to 2021.

Raisi further emerged into the national spotlight in 2016, when he was appointed as the custodian of the powerful and wealthy Astan-e Ghods Razavi (or Imam Reza shrine foundation) in his home city of Mashhad until 2019, following the death of its longtime former custodian Abbas Vaez-Tabasi.

Despite his recent emergence from relative obscurity at the time, much of the principlist political current in Iran quickly consolidated around him to contest the 2017 presidential election. The principlists, who are one of the two main political currents in the Islamic Republic alongside the so-called moderates, derive this name from their commitment to the principles of the Islamic Revolution, but are more commonly referred to in English-language media as “conservatives” or “hardliners”. Raisi lost the election to then incumbent President Hassan Rouhani that year by a wide margin.

He ran for president again in 2021, this time winning the election in June of that year, and assumed office in August. This presidential election featured a 48.8 percent voter turnout rate - the lowest for such elections in the history of the Islamic Republic - and is believed by many to have been engineered by the upper echelons of the system to ensure Raisi’s victory, including through the disqualification of potentially viable rivals from standing for the race by the Council of Guardians.

In contrast to all of his predecessors since 1989, President Raisi exhibited total loyalty and obedience to the person and thought of Ayatollah Khamenei, a desirable characteristics among principlists in Iran referred to as velayat madari. His presidency was therefore regarded with some enthusiasm by the committed principlist supporters of the Islamic Republic.

But President Raisi was likely viewed less favorably by other segments of the Iranian political establishment and society for a range of reasons, including the perception that he was not a strong or charismatic political figure; his limited senior executive and administrative experience prior to become president; questions surrounding the level of his educational attainment and religious qualifications; and his direct involvement with the mass executions of 1988, and subsequent role in human rights violations and repression Iran in his capacity as a senior judiciary official and president.

The Raisi government, more generally, had very few unambiguous successes to its name, keeping in mind the limited power of the presidency in Iran, and bad prevailing structural conditions in the country.1 The economy has not faired well, with the currency accelerating its downward slide against the dollar, and the purchasing power of the average Iranian citizen continuing to erode. However, his government did make notable efforts to increase the non-oil revenue through taxation.

Iran under the Raisi government has also faced profound social unrest and repression, including what were arguably the most widespread, persistent, and violent demonstrations since the revolution from September to December 2022, following the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody after she was arrested for allegedly improper hijab. Under its tenure, Iranians have continued to face severe limits on their social and political freedoms, and in some instances like the hijab and cyberspace, the situation appears to be deteriorating further.

The Raisi government also pursued a foreign policy that emphasized relations with neighbors in West Asia, states of the Global South, and Russia and China. In this context, his government was an important element of broader efforts by the Islamic Republic, like the agreement brokered by China that normalized relations with Saudi Arabia in 2023, membership with the Eurasian regional security bloc the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) the same year, and membership in the global economic bloc BRICS in 2024.

Who was foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian?

Hossein Amir-Abdollahian was born in Damghan, Semnan province, in 1964. As a young adult he pursued his bachelors degree at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’s School of International Relations from 1987 to 1991 and joined the ministry at the end of his studies. He obtained his masters in international relations at the University of Tehran in 1996 and doctorate in the same field from there in 2010.

He quickly ascended the ministry’s ranks to hold numerous senior positions, including ambassador to Bahrain from 2007 to 2010, director general for the Persian Gulf and Middle East from 2010 to 2011, and deputy foreign minister for Arab and African Affairs from 2011 to 2016.

Amir-Abdollahian’s career was boosted by relationships with key political figures in Iran, including the now deceased IRGC-JF commander Major General Ghasem Soleimani, whom he worked under in his capacity as a member of Iran’s negotiating team in the trilateral talks between the United States, Iran, and Iraq in 2007.

After departing from the foreign ministry in 2016, possibly due to a falling out with then foreign minister Javad Zarif, he served as special assistant to the speaker of parliament and the director general for international affairs of the parliament from 2016 to 2021, first under Ali Larijani, and later Ghalibaf.

Amir-Abdollahian’s close associations with the IRGC, Jerusalem Force, and the principlists, as well as emphasis by the incoming president on improving relations with regional neighbors, are believed to have helped him clinch the role of foreign minister in 2021. Although Amir-Abdollahian oversaw a broad portfolio as foreign minister, his main focus remained on West Asia. He is believed to have played a role in the agreement to normalize relations with Saudi Arabia and was very active in the regional diplomacy surrounding the Gaza war prior to his death.

Iran also joined the SCO and BRICS during Amir-Abdollahian’s tenure. Despite the symbolic significance of such moves for the Islamic Republic, it remains to be seen what concrete benefits Iran can derive from this expanded network of relationships.

What happens next?

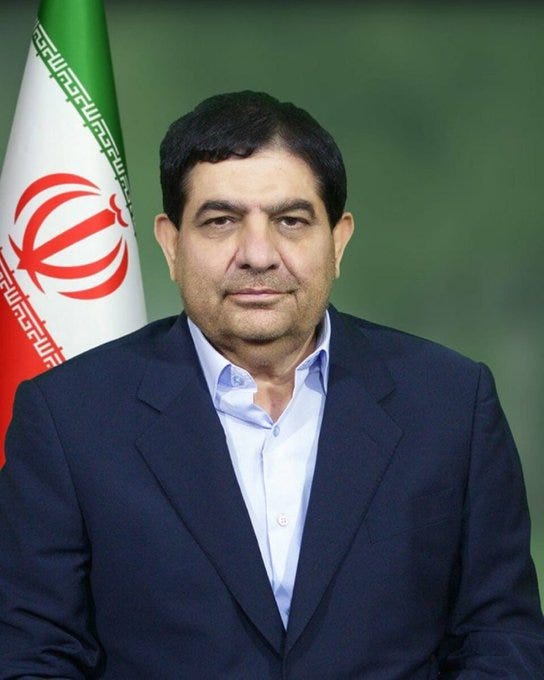

According to Article 131 of the Iranian Constitution, following the death of a president, the first vice president assumes his authorities and responsibilities with the approval of the Leader. Subsequently, a council is formed composed of the first vice president, speaker of parliament, and chief justice, who are required to organize the election of a new president within a period of a maximum of 50 days.

The first vice president, Mohammad Mokhber, is now acting president. He was born to a clerical family in the city of Dezful, Khuzestan province, in 1955, and served in the IRGC medical corps in the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). After the war he served in mid-level administrative and economic positions before being appointed as the head of the Headquarters for the Execution of the Orders of the Imam (usually referred to in Persian as Setad) from 2007 to 2021. This entity operates as a charitable organization and business conglomerate under the direct supervision of the Office of the Leader. This influential perch was a stepping stone to the first vice presidency for Mokhber, who besides political and foreign policy duties, mainly focused on economic affairs.

The Ministry of Interior election headquarters has circulated a preliminary schedule foreseeing presidential elections on an accelerated basis but subject to modification:

Candidate registration will take place between 30 May and 03 June;

The Council of Guardians will vet potential candidates from 04 to 10 June;

The interior ministry will announce the approved candidates on 11 June;

Campaign is then expected to take place from 11 to 26 June;

Election day is expected to be held on 28 June;

If no candidate wins a majority, then a second round of voting will take place on 05 July to elect a president in line with the constitutionally mandated 50 day limit;

Critically, while the term of President Raisi was set to conclude in August 2025, the newly elected president will serve a four year term;

Interestingly, this will not only synchronize the presidential, parliamentary, and Assembly of Experts election cycles to take place in the same year, but also synchronize the US and Iran’s presidential elections to be held the same year.

Ali Bagheri Kani is the acting foreign minister following the death of Amir-Abdollahian. The former, who served as deputy foreign minister for political affairs prior to his boss’s passing, is a strong contender to stay on in this new role.

Bagheri Kani has served as Iran’s lead nuclear negotiator and, despite being a critic of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and his association with the principlists, took the lead in the talks that resulted in the US-Iran “non-agreement” in 2023 that informally and in a limited fashion dealt with some nuclear, regional security, sanctions, and humanitarian issues.

He previously served as the deputy secretary for Iran’s Supreme National Security Council under Saeed Jalili, who unsuccessfully managed nuclear talks from 2008 to 2013, and was the chairman of the failed presidential campaign for Jalili in the 2013 presidential election.

Bagheri Kani is the scion of a very prominent clerical family in the Islamic Republic, and a graduate of Imam Sadegh University, which has trained a large cohort of the younger cadres and functionaries of the system and was founded and led by his late uncle Mohammad Reza Mahdavi Kani from 1983 to 2014.

Who could be Iran’s next president?

The ever-shrinking circle of power in the Islamic Republic will have to decide between attempting to mobilize the public and increasing popular participation in the upcoming election, or once again engineering the selection of its favored candidate as it most recently did with President Raisi in the 2021 vote.

The system in Iran is loathe to permit a truly free and open election. But without at a minimum permitting viable and potentially popular candidates from the so-called “moderate” political current in Iran to participate, and a somewhat open political atmosphere around election time, it is like to continue to face headwinds against popular participation: According to Iranian government statistics the voter participation rate in the 2017 presidential election was just over 73 percent. It fell precipitously during the 2021 presidential election to around 49 percent.

This sharp decline cannot be mainly attributed to other factors like the coronavirus pandemic that plagued the country and the world for much of 2020 and 2021: While the voter participation rate in the 2020 parliamentary elections was around 43 percent, already down from the 2016 elections when it was 63 percent, it declined further during this year’s parliamentary elections to approximately 41 percent, with invalid votes making up five percent of the total vote count and possibly even higher according to some media reports. In the second round of this year’s election on 10 May, voter turnout in Tehran, the capital city of Iran and its largest constituency, may have been as low as eight percent.

The waning legitimacy of the Islamic Republic has been further battered and bruised by cyclical mass protests in 2018, 2019, and 2022 that have become more widespread, persistent, and violent over time. The 2018 and 2019 demonstrations appear to have been mainly motivated by discontent around the weak economy and declining standard of living. The 2022 ones, in contrast, sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini, focused more on the the lack of social and political freedoms in the country.

These mass protests share at least two key traits in common. First, they have been composed of overwhelmingly young protestors confronted with a grim future. Second, in contrast to the 2009 Green Movement protests that were arguably part of a radical reformist political project, these demonstrations have unambiguously called for the overthrow of the Islamic Republic and been more violent towards the state. The resultant harsh crackdown by the system, including killing of hundreds of protestors, wounding thousands, and arrests in similarly high numbers, has created a sense of rage and anguish across a large segment of society that seethes just below the surface.

Some of the slogans by the demonstrators since 2018 have made it clear that they increasingly reject the dichotomous choice provided to them in elections by the Islamic Republic between reformists and conservatives, or moderates and hardliners. They see the system, and not one political current or another, as the problem. Against this background, it’s unclear how effective the tactic of allowing limited competition between viable candidates from the different political currents in the upcoming would be in terms of boosting popular participation.

Nor do I think the centers of power in the Islamic Republic have any desire to do so, even if it would work. My assessment is that despite the clear warning signs, they are likely to stay the course and engineer the selection of a favored candidate that will continue to pave the path for a successful transition that best preserves the (unsustainable) status-quo favorable to the principlists sitting at the heart of power.

Any potentially viable “moderate” candidates are therefore likely to be disqualified from participating in the presidential election by the Council of Guardians or otherwise handicapped from effectively electioneering.

This does not discount some measure of competition among principlists. A principlist candidate able to step into President Raisi’s shoes has yet to emerge. To become president, such a candidate would need to consolidate principlist support behind himself, possess senior executive and administrative experience, and have the ambition and desire.

Acting president Mokhber is one obvious candidate. Another possibility is speaker of parliament Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, who has steadily climbed the rungs of power in Iran and amassed a vast wealth of executive and administrative experience across a range of sensitive and prominent positions in security and politics.

Ghalibaf joined the IRGC after the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War and quickly climbed the ranks to become a division commander. He had a successful military career following the war, serving from 1989 to 2000 as the deputy commander of the Mobilization Resistance Force (more commonly referred to as the Basij), commander of the Khatam al-Anbia Construction Headquarters (an IRGC military engineering arm and a major project contractor today), and commander of the IRGC Air Force (today called the Aerospace Force). He left the IRGC to serve as chief of police or the Law Enforcement Force (LEF) from 2000 to 2005, and was elected as the mayor of Tehran from 2005 to 2017, placing him in the national political spotlight. Ghalibaf has served as speaker of parliament since 2020, but has a demonstrated ambition to be president: He ran for the position in the 2005, 2013, and 2017 presidential elections.

Despite his wealth of experience and ambition, Ghalibaf also comes with considerable baggage. He lost the first two presidential elections that he contested and withdrew from the third in favor of Raisi. He has also had several corruption scandals that have implicated himself personally, his family, and allies. These scandals, in addition to his affiliation with a less hardline faction of principlists who have been engaged in a protracted conflict with their more hardline counterparts in parliament, make it less likely that principlists as a whole will consolidate around him.

Finally, there is evidence that even supporters of the system might not turn out to vote for him in significant number: Despite his stature, he only received the fourth most number of votes of any candidate in Tehran during this year’s parliamentary elections, compared to his first place finish in the 2020 elections. Given this performance and the composition of the incoming parliament, he may not serve as speaker in its upcoming term.

The various factions of Iran’s political currents did not expect to have elections until 2025, and as such, do not necessarily have candidates ready to go, nor have they had the opportunity to consolidate around a single candidate within their currents. So the field remains wide open, and if a clear principlist front runner does not emerge, we may see a heated competition among them to be Iran’s next president.

Could President Raisi’s death change Iran’s policies?

The overall direction of the Islamic Republic in domestic politics and foreign policy is set by the Leader, who also directly selects or indirectly influences the selection of the heads of all of the major elected and unelected centers of power in Iran, thereby shaping high-level policy and personnel at every level of the system.

Within the boundaries placed by the Leader, the centers of power can individually set policy in a domain under their purview, or come together to collectively shape policy in a consensus-building process, for example as it unfolds in the Supreme National Security Council. Our default assumption should therefore be the continuation of the status-quo in domestic politics and foreign policy, despite the deaths of President Raisi and Amir-Abdollahian, although some avenues for adjustments do exist.

The Iranian presidency is a nominally elected center of power which can play a strong role in shaping and executing policy to various degrees across a range of domains, including domestic politics, the economy, foreign policy, and security.

The Raisi government has been the presidential administration to most closely adhere to the line and tone set by the Ayatollah Khamenei since 1989. This, alongside the supposed unification of all centers of power in Iran under the control of the principlists (who are supposed to very closely align with the Leader) has in theory created one of the most unified and coherent governments in the history of the Islamic Republic. In practice, there has been no dearth of infighting among principlists, and policy coherence across every domain is highly debatable.

Nonetheless, the election of an assertive new president with an experienced team who can deftly manipulate the levers of power at their disposal, may adjust policies and the elite consensus in meaningful ways that are difficult to predict right now. For example, should principlists fail to come to agreement on a candidate to put forward, the endemic infighting in this political current could spill out into the open, generating unexpected competition that may translate to unexpected policy horizons.

Or, the Leader and other elements of the Islamic Republic who engineered Raisi’s election could elevate such an individual in order to make a course correction that restores some of the system’s badly damaged legitimacy at home, boosts the economy, and lowers tensions abroad. But any sudden change in direction, despite the dire state of affairs in the country, does not appear likely at the moment.

How does President Raisi’s death affect the Leader succession process?

One reason the Leader and other powerful elements of the system might be hesitant to rock the boat at this juncture is the prospect of a leadership succession on the horizon for Iran: Ayatollah Khamenei is 85 years old, and it is not inconceivable that he may become deceased or incapacitated in the next few years, leading to a succession process to unfold.

President Raisi appears to have been groomed for and elevated to his final role at least in part because he was viewed as a senior figure who was reliably subservient to the Leader, both in the presidency during Ayatollah Khamenei’s lifetime, as well as likely following his death during a succession process.

Some viewed his rapid rise through a coterie of the Islamic Republic’s most influential positions in a relatively short span of time as a sign of the special favor bestowed on him by Ayatollah Khamenei and that he was being groomed for the position of Leader.

It is difficult to say if this was the case with certainty. Even if he was previously a top contender for the role, his lack of charisma, limited speaking ability, and lackluster performance as president must have led to some reconsideration about whether he was truly the right person for the job.

Nonetheless, President Raisi’s death may represent a disruption of the effort by Ayatollah Khamenei and key elements of the system to manage the political environment ahead of a succession so as to better shape the succession itself.

Furthermore, a snap election to select a new president amid a crisis of legitimacy and anemic voter turnout is a tall order that creates greater uncertainties for the political conditions in the country in advance of any succession.

Some have argued that President Raisi’s death has opened up a clear pathway to becoming Leader for Mojtaba Khamenei, a son of Ayatollah Khamenei, who plays an influential behind the scenes role in national security in his father’s office.

I regard this too with some skepticism. The Islamic Revolution of 1979 overthrew the shah and was at least on the surface driven by an anti-monarchial animus. A son succeeding his father too much resembles a monarchy, and smacks of the nepotism that is endemic to the Islamic Republic.

When it comes to the Leader role, Mojtaba also lacks senior executive and administrative experience, grasp of the rough-and-tumble of national politics, some level of stature among the Iranian Shia clergy, and a visible public profile.

Ayatollah Khamenei is focused on consolidating the status-quo and his legacy during a succession, and will look for a suitable Leader candidate with the right characteristics who can do this. This does not rule out Mojtaba playing an important role during the succession, or becoming a more viable Leader candidate in the future.

In fact, the future Leader, if the next iteration of the Islamic Republic retains this position unchanged, may not clearly appear as a candidate on the political stage in Iran until close to the time that a succession is at hand.

The experience of Ayatollah Khamenei’s rather unexpected rise to this position in 1989, or the rapid ascent of the last four presidents to their stations from relative obscurity, may provide a blueprint for how the leadership succession could unfold.

Candidates who appear viable today, may be far less so in one, two, or five years because they unexpectedly die or are sidelined. This is borne out by the experience of the first decade after the Islamic Revolution from 1979 to 1989.

For example, the Ayatollahs Morteza Motahari and Mohammad Beheshti had the potential to become Leader given their considerable religious and political stature after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Islamic Republic’s first Leader, passed away. But they were assassinated in 1979 and 1981, respectively, and did not outlive him.

Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri had a similarly notable stature, and was even designated as Deputy Leader in line to succeed Ayatollah Khomeini from 1985 to 1989, but was politically sideline shortly before the succession.

The Iranian presidential election, set to unfold between now and early July, will resolve many of the questions and issues in this article, and be revealing of others. We should remain vigilant for clues about the future.

President Raisi took power in a fraught context, including in the aftermath of the US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018, and the Covid-19 pandemic which was ongoing at the time, among other conditions facing the country.